Teaching a New Assistant How to Be Useful

Lessons from a day of configuring OpenClaw permissions and constraints

I spent most of yesterday configuring an AI assistant (OpenClaw) to help me be more deliberate about scheduling time with friends. To do so, I integrated AI to work with my calendars, contacts, messaging, and various other pieces of my digital life. What struck me, as the hours went by, wasn’t the technical complexity. (There was a bit of that!). It was how much this process revealed about what I actually value, what I’m trying to preserve, and where I want to draw boundaries.

This isn’t a how-to guide. There are better places to find installation instructions. What I want to explore is what it meant to me to bring an automated system into my thoughts about scheduling, communication, and “memory” (I’ll explain more on this later) and what I’m learning about myself in the process.

Care with permissions

The first thing I noticed when setting up this kind of system was how many times I had to decide what to allow. There were all sorts of scary privileges, including Full Disk Access, Calendar permissions, Contact access, and Message sending. Each prompt forced me to question whether I really trusted an automated AI agent with that portion of my digital life.

What was interesting to me was how those decisions accumulate. It’s easy to say “yes” to everything when I’m just trying to get something working. I found it harder (and more valuable) to pause at each permission and ask what I was actually comfortable with. I found myself saying “no” more often than I expected. Not because I’ve yet had an opportunity to build any sort of distrust in the system, but because I wanted to be intentional about what I was opening up.

For example, I was hesitant to let AI just control a web browser on my behalf, but when I realized I needed it to be able to determine the commute time between my home and suggested places to visit I decided to use a Google Maps API key so I could enable my agent the could use of a specific skill to look up places.

This mirrors something I’ve noticed in other domains. The systems that I have used tended to expand their reach unless I took some effort to actively constrain them. The default always seems to offer more access, more integration, and more data flow. Maintaining boundaries requires ongoing effort. Like getting rid of extra stuff in the home, it’s not a one-time decision but a continuous practice.

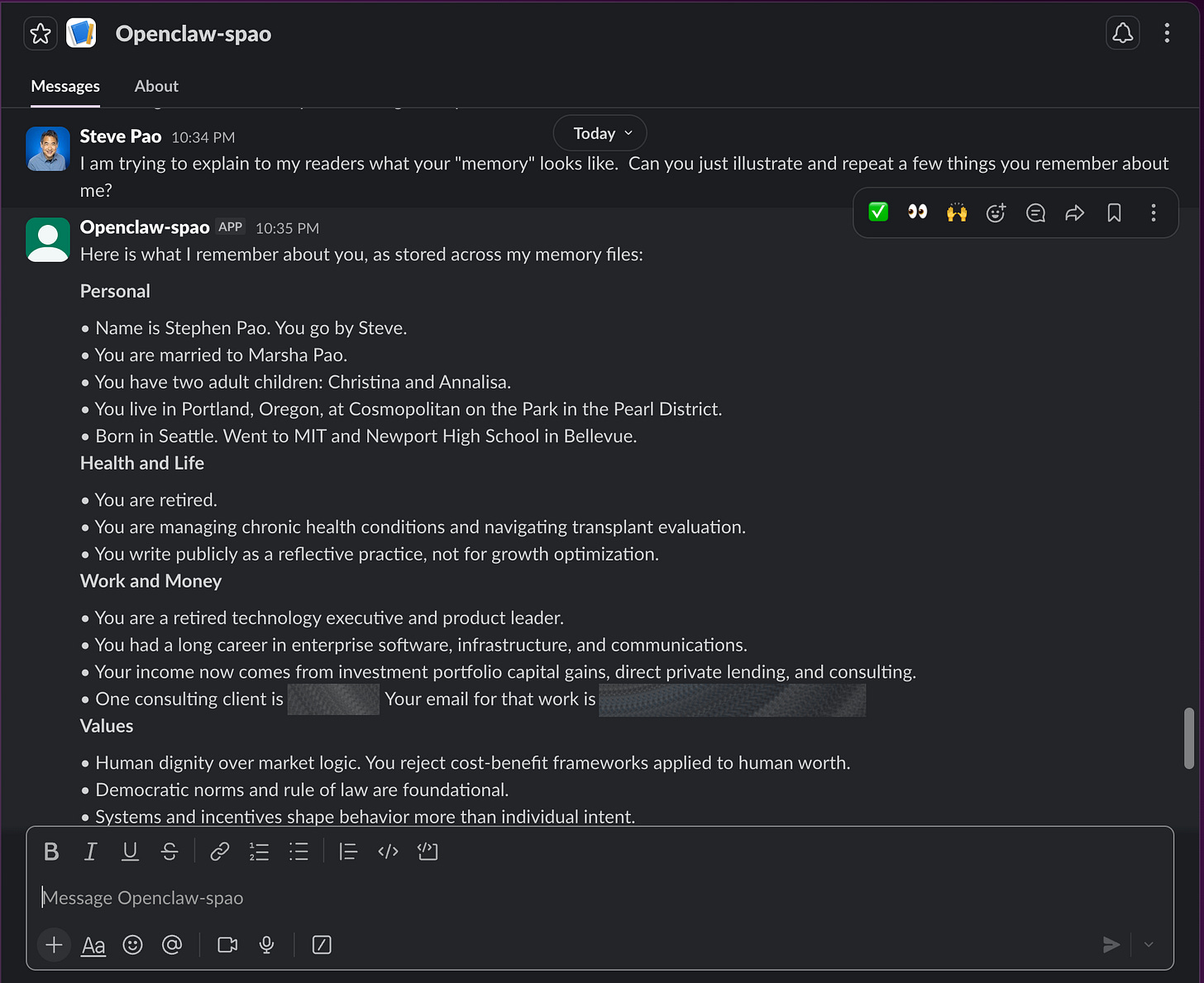

Deciding what is remembered

One of the more involved parts of today’s work was establishing how the assistant should remember things. There’s a workspace where it keeps files, and there are daily memory logs, and there’s a longer-term memory file for things that persist across sessions. Designing what goes where forced me to think about what actually matters enough for the system to remember.

I found myself distinguishing between tactical information, including schedules, contact details, and basic workflows versus deeper patterns like how I make decisions, what I prioritize when tradeoffs are required, and the tone and voice I use when I write. These deeper patterns aren’t facts so much as they are aspects of character, and somehow codifying them into instructions felt strangely personal.

A part of me just wanted to put everything in. To document every preference, every heuristic, every quirk, but I resisted this temptation. I’ve found that part of what makes human memory useful is that it’s selective. I think we tend to remember what matters and let the rest fade. An assistant with perfect recall of everything I’ve ever said would likely be overwhelming, not helpful. I tried to be thoughtful about what deserved persistence.

Controlling communication to the assistant

Perhaps the most consequential decision I made yesterday concerned messaging. I wanted the assistant to be able to receive iMessages from a group of friends also playing with their AI assistants, but I didn’t want anyone in that group to be able to command my assistant. Only I should be able to do that.

Setting this up required understanding how the system distinguishes between receiving data and executing instructions. The technical implementation was straightforward enough. I was able to tell my AI assistant in plain English to modify its own behavior and restart its software. Still, the underlying principle felt important. I was creating a boundary between conversation and action.

This distinction matters more broadly. We live in a world where systems increasingly blur the line between conversation and action. Alexa is probably the most disruptive example of something that does both in a way that can be either useful or frightening. I like being able to ask my Echo about the weather forecast. I don’t want it to buy things for me. Personally, I’ve found value in maintaining a clear separation between what a system can talk about versus what it can actually do on our behalf.

The basic test was to pretend to be someone else by logging in with a different Apple ID (and thus iMessage account) to try to command the assistant. It refused, citing the policy. I then sent the same request from my authorized account, and it worked. The boundary held. This might seem like a small thing, but it was an important and deliberate constraint on automation’s reach, even when adopting the default behavior to enable broader access would have been easier.

Informing AI decisions

Throughout this process, I kept returning to a question of what I was really trying to optimize for, whether it be efficiency, convenience, or just the ability to offload cognitive burden. While all of those points matter to me, they didn’t quite fit.

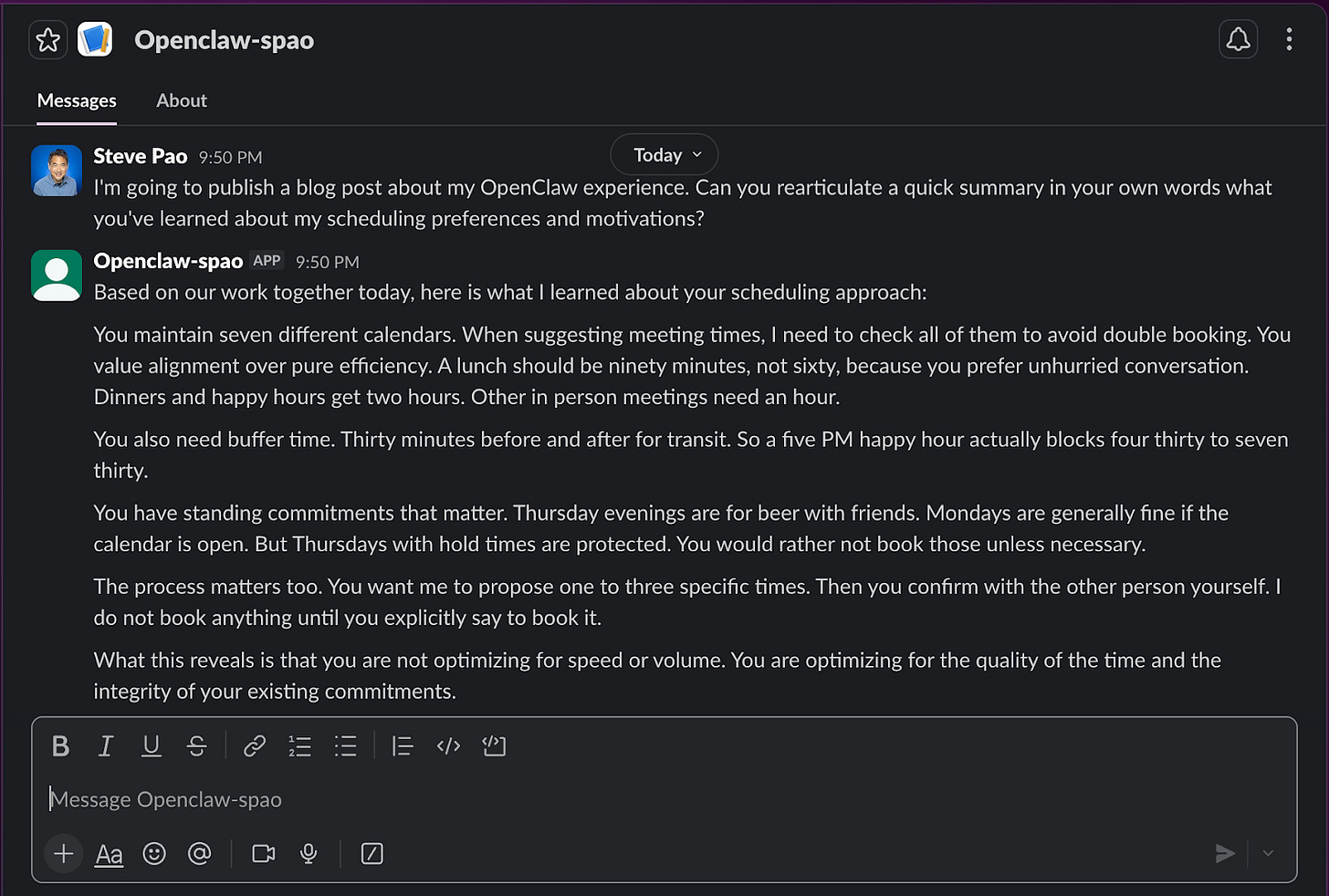

What I found myself optimizing for was something closer to alignment. I wanted an assistant that understood not just my preferences, but how my values animated those preferences. Logistically, the assistant should know to check multiple calendars before suggesting a meeting time because I care about not just double-booking myself over different consulting commitments but also those made personally. It should know to suggest 90 minutes for lunch rather than an hour because I value unhurried conversation. It should also know that I’d prefer not to book Thursday evenings for happy hours or other events involving alcohol because I already have beers every Thursday afternoon with friends.

These aren’t complicated rules. A traditional calendar system could handle most of them, but they accumulate. The combination of these rules reveals something about how I want to live. Teaching my rules to a system is forcing me to articulate things I hadn’t fully spelled out before.

There’s a feedback loop here that’s worth noting. When I have to explain my preferences to an AI assistant, I begin to realize which ones are genuine and which are just habits. I discovered that some of my scheduling patterns were accidents of history rather than intentional choices. The process of encoding them made me reconsider whether I actually wanted to keep them.

Not “auto-magic”

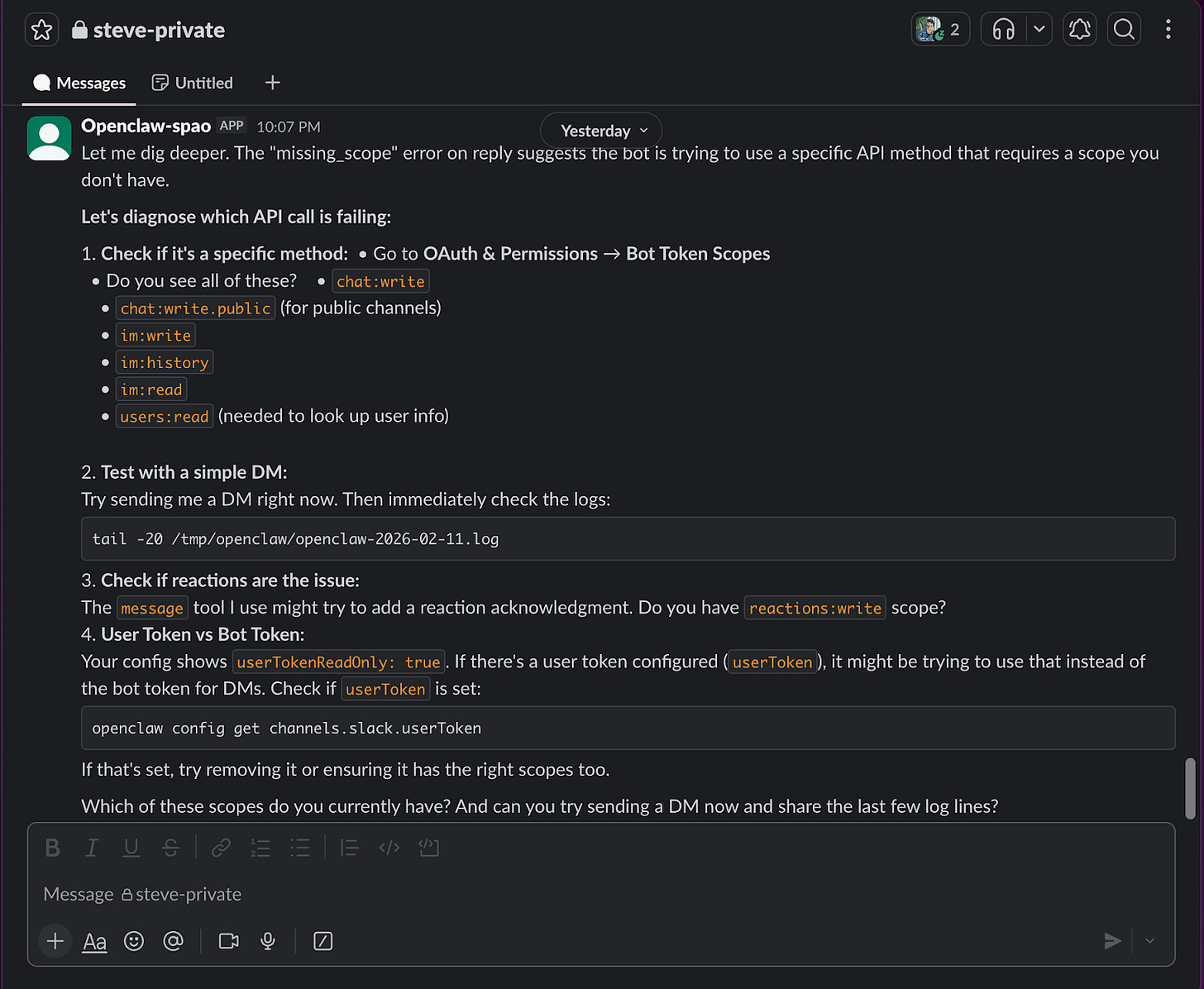

By the end of the day, the assistant and I had settled into a rhythm. I would ask it to check calendars, add contacts, and configure permissions. It would confirm, execute, and report back. The exchange felt natural in a way that surprised me.

Still, there were also moments of friction that reminded me that this was still a nascent technology. There were many technical things that happened, which may mean nothing to non-technical observers. Security around a chat session required a pairing code that expired before I could approve it. A random Slack permission that didn’t take effect until I restarted the service. The realization that Full Disk Access meant something different depending on how a service was launched on the MacOS.

These aren’t complaints. They’re observations about where the seams show. The technology works well enough to be useful but not so seamlessly that I forget it’s complex technology. I suppose there’s part of me that appreciates some of that friction. It keeps my guard up and prevents the kind of complacency that comes when technology feels too much like magic.

What Comes Next

I don’t know yet how this experiment with an AI assistant will evolve. Today was about setup and configuration, as well as establishing boundaries and workflows. The real test will be ongoing use. Will I trust the assistant with more over time, or will I find myself constraining it further? Will the convenience outweigh the vigilance required to maintain appropriate boundaries?

These aren’t questions I can answer today. What I can say is that the process of setting this up taught me something about how I want to relate to automated systems. I don’t want the system to replace judgement, but rather extend it. I don’t want the system to operate like a black box that makes decisions for me but rather as a tool that I have deliberately configured to reflect what I value.

The assistant is running now. The calendars are synced, the contacts are imported, permissions are set, and messages are flowing to the right places with the right constraints. So, for now, it’s an easier way to do some little things to save me some time. However, I’ve realized that I’m also making a set of choices about the role I want technology to play in my life, stated explicitly and intentionally in the form of rules.

That intentionality is what I’ll try to remember when the novelty of an AI assistant has worn off and I’m just using the assistant naturally in my daily life. The boundaries matter. The constraints matter. The ongoing work of maintaining them matters. Because in the end, that’s what keeps the tool from becoming something that uses us, rather than the other way around.

Steve - good write up. I’ve been using Claude Code + Obsidian and loving it! I’m still unsure about moving to OpenClaw due to the security reasons. I need to define what my killer use cases are before I take that next step. Thanks for sharing and hope you’re doing well!