Questions I’ve Been Asking Myself

Another step in the transplant journey

Thank you to everyone who has reached out with support after I shared the latest on my kidney disease. Many of you asked thoughtful questions, the same ones I’ve been asking nephrologists, transplant coordinators, nurses, and educators at OHSU, Strive Health, and Kidney Smart, among others.

I’m not an expert. But I wanted to capture where I am right now as I try to understand three big themes: cost, donation, and life purpose. These questions have pushed me not just into medical territory but into social ethics, meaning, and what it means to “be enough.”

Costs

If I qualify for a kidney transplant, the procedure and lifelong medications will be extremely expensive. The surgery alone sits in the six‑figure range, and immunosuppressants cost thousands per month for the rest of my life.

My first reaction was:

“How should I feel about being this expensive?”

Last year, my insurer processed nearly $100K of claims and paid out about 45%. My current medications (Ozempic, Jardiance, Kerendia, et al) are already more than $2,000 per month before insurance. In our capitalist framing of the world, it’s hard not to see myself as creating an “expense line.”

But my nurse at Strive Health made an excellent point. This burden is structural, not personal. I’m simply trying to stay alive. Prices reflect the design of the U.S. healthcare system, not the value of my life.

Health‑policy researchers reinforce this concept. The U.S. doesn’t spend more because patients like me use too much care, but because our system charges higher prices. Costs are a policy and pricing problem, not a moral referendum on individual worth.

So the perspective that I am actively learning is that my care sits inside a social contract, not an individual ledger.

I don’t have to prove I’m “worth it.” Receiving necessary medical care is not a debt I must repay.

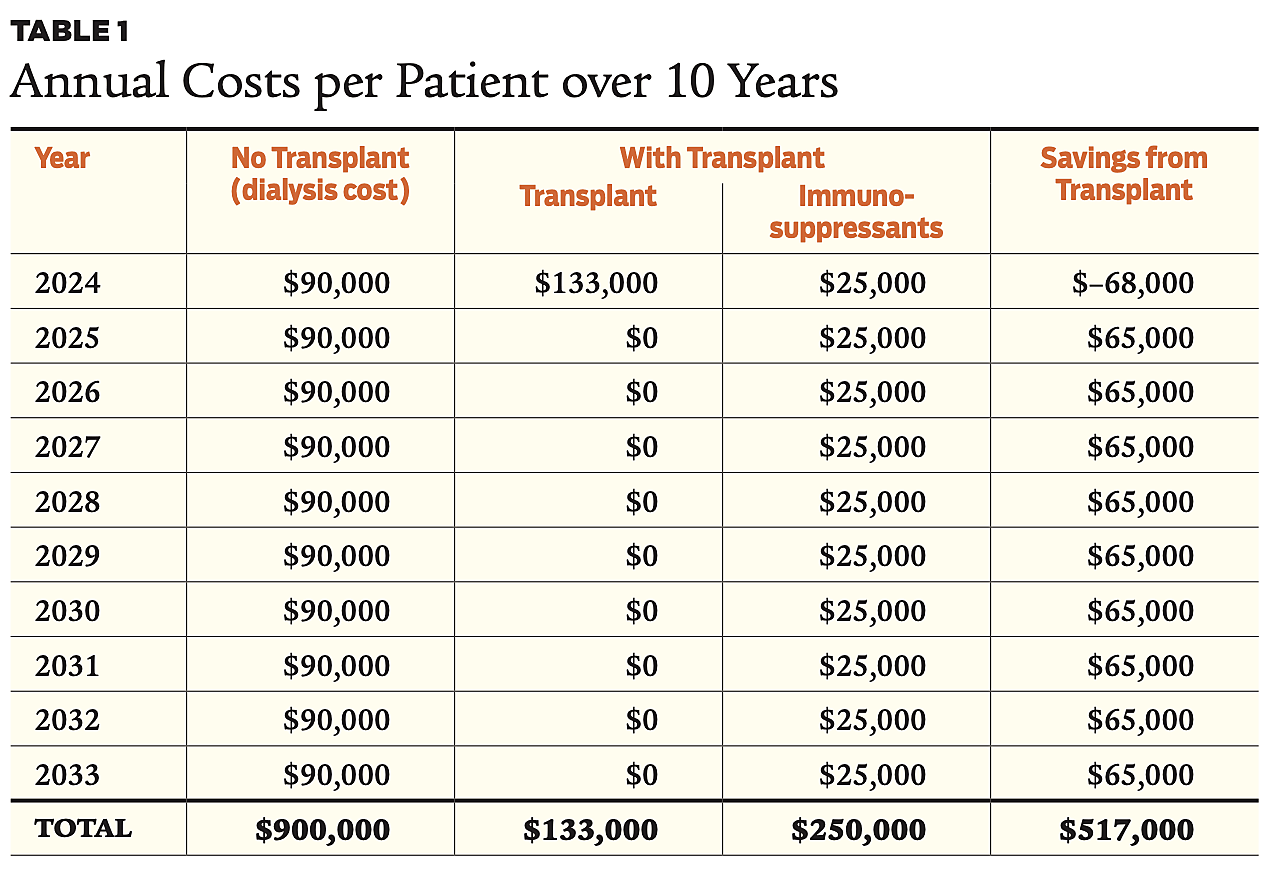

A side note I found comforting was that transplantation is actually much more cost‑effective than long‑term dialysis. Even with the upfront cost of surgery and lifelong meds, transplant recipients typically generate significant savings to the health system over time.

Of course, this cost justification in no way justifies my existence. However, at least it does provide some insight into the workings of the system that removes some psychological weight on me.

Donation as Gift Exchange

If I qualify, the strong recommendation is to seek a living donor. In Oregon, the wait for a deceased donor kidney is more than five years, and fewer than half of wait‑listed patients receive one. Living donor kidneys also tend to last longer, roughly 15 years instead of about 10.

So I’ve had to ask myself:

Why would anyone donate a kidney? And why would I accept something that feels so enormous?

My nurse’s answer reframed the question. Donor motivation, he said, comes from meaning and from a desire to lessen someone’s suffering, to tangibly help, and to act out personal values. He mentioned several nurses in his own practice who have donated kidneys to people they didn’t even know.

This concept aligns with something I’ve been thinking about in a political context, the idea of abundance. Generosity is not a zero‑sum transfer but an expression of shared humanity. Under this lens, donation isn’t a “sacrifice that must be repaid.” It’s a gift exchange: the donor offers a gift of life, and the recipient gives back the gift of meaning.

The research backs this up. Many donors describe donation as one of the most fulfilling experiences of their lives.

“Many positive comments identified donation as one of the most fulfilling experiences in the donor’s life. For example, donors wrote, ‘Organ donation was the most meaningful event of my life after becoming a father’ and ‘Being able to help my sister was the high point of my life.’ Other comments indicating a positive association between donation and SWL [Satisfaction with Life] often focused on benefits to the donor, such as ‘Donation gave me a sense of direction and purpose for my life’ and, ‘I have more self-esteem after donation than I ever had my whole life’ or comments about an enhanced relationship with the recipient.”

—Messersmith, Gross, et al, “Satisfaction With Life Among Living Kidney Donors: A RELIVE Study of Long-Term Donor Outcomes.” Transplantation. PMCID: PMC4333130.

Of course, there remains a minority of donors who describe more difficult or complicated emotional outcomes, especially when family dynamics were strained or when the recipient had a poor medical outcome.

“Negative comments focused on questioning whether the decision was actually a good choice and on poor relationships with others. For example, one donor, whose donation to an in-law was not supported by her husband, wrote, ‘It is very difficult to feel resented for something like this.’ Another, whose recipient became ill during recovery and died within a year of transplant, wrote ‘I feel the whole affair was a waste of life, much pain and of course expense.’”

—Messersmith, Gross, et al, “Satisfaction With Life Among Living Kidney Donors: A RELIVE Study of Long-Term Donor Outcomes.” Transplantation. PMCID: PMC4333130.

These more difficult outcomes underscore why donor screening is incredibly thorough and why donor protections, such as priority for future transplants if they ever need one, are built into the system.

Financially, there are still costs, including travel, time off work, and logistics. The education materials describe programs like (NLDAC, Donor Shield from the National Kidney Registry) that can help in certain situations. The donation ecosystem essentially tries to foster people’s desire to help while clearing the roadblocks.

I’m still wrapping my mind around the psychosocial aspects of all this. But I already feel deep gratitude for the people who have donated and for those who might consider it.

Life Purpose

Even if the costs are justified, and donors often experience profound meaning, one final question lingers for me:

Do I need to do something more with my life if I receive a kidney?

Or more profoundly:

Am I enough as I am?

This has come up in multiple conversations with my care team, and I’ll summarize the main points I have walked away with.

Taking care of myself, The most fundamental way to honor the gift is to follow the transplant protocol: take the medications, attend follow‑ups, and maintain the healthiest lifestyle I can.

Belonging, I don’t need to reinvent myself into a superhero. The goal is to return to the life and relationships that already matter to me, supported rather than overshadowed by the transplant.

Shared participation. There’s a societal reciprocity that keeps the system working. Sharing my story here on Substack and hopefully supporting others in their journeys is a start. Being registered as a deceased donor is another way of participating in that broader social fabric. I’ve already committed to donating my brain and spinal cord to UCSF’s Memory and Aging Center and am exploring OHSU’s body donation program as well.

This is all slowly starting to make sense. A key part of my mental health journey has been recognizing that capitalist logic doesn’t apply here. Care is not a debt. I don’t owe the world a “return” in the form of exceptional productivity or heroism. Being the best version of myself should really be enough.

At the same time, I can express gratitude through abundance by offering mentorship, advocacy, or support in parts of life where I have something to give. This isn’t “repayment” but rather just generosity.

Netting It Out

For me, the purpose of writing all of this out is to help me internalize what I am being told. The goal of my ongoing care is to let me continue living the life I already value, to experience the small joys, to be with the people who matter to me, and to honor the kidney by caring for it.

There’s no return‑on‑investment I need to produce, a balance sheet to justify, or heroic transformation required.

That is enough. And I am enough.