Not Looking Away

Why I am getting more civically engaged

I have written before about exercising my freedom of speech, calling legislators, attending town hall meetings, and even participating in protests. This year, I've participated in the #HandsOff, #NoKings, and #GoodTroubleLivesOn protests here in Portland.

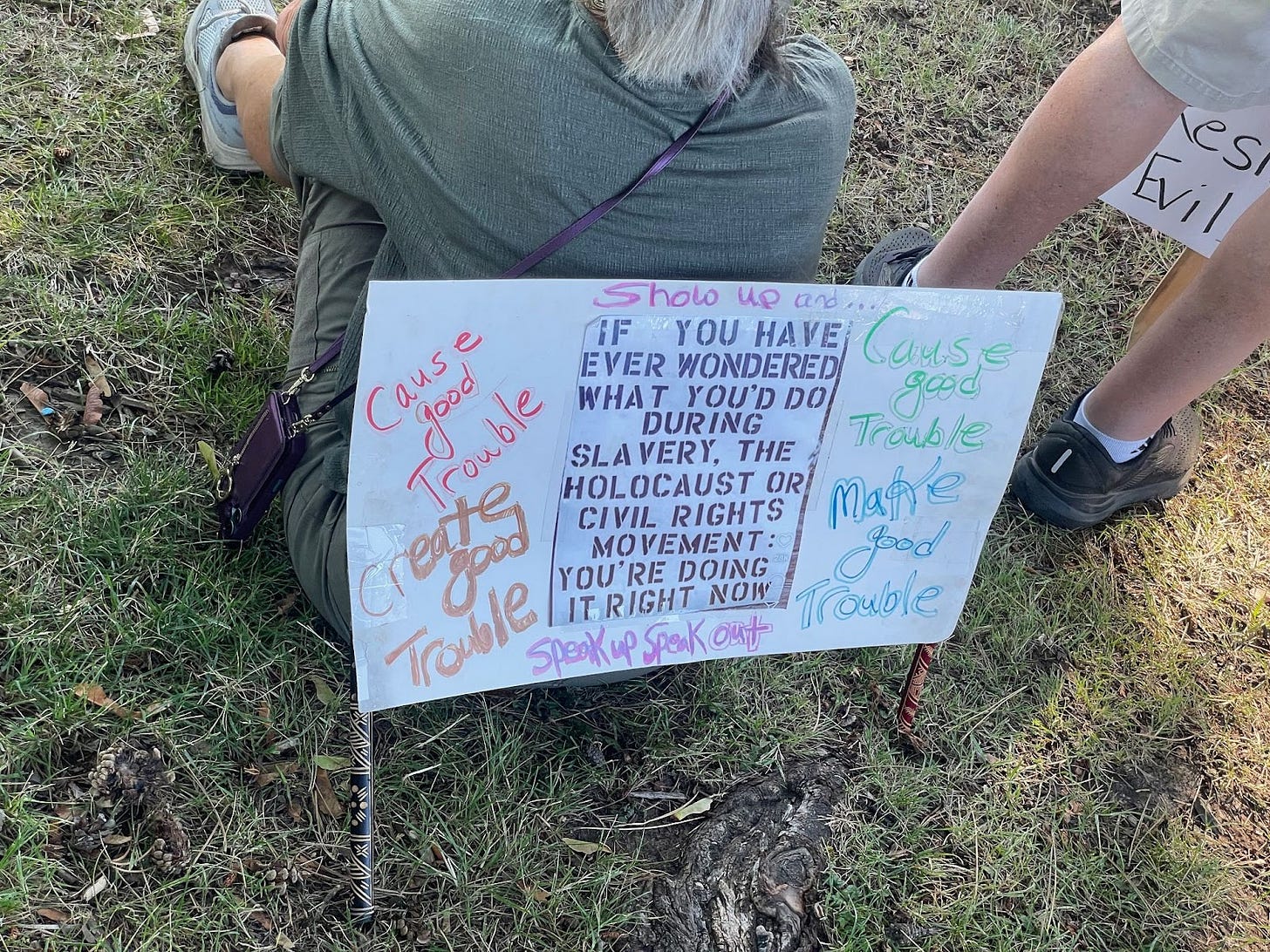

I don't do these things because I think they will fix everything overnight. I participate because I believe silence has a cost, and history has taught us that this cost can be lasting. At the #GoodTroubleLivesOn protest, I saw a sign that crystallized what I've been feeling.

A Conversation at 30,000 Feet

Years ago, during my working days when I traveled more frequently, I found myself upgraded to business class on a long flight. The German gentleman beside me had also been upgraded, and our shared excitement led to one of those unexpectedly profound conversations that can happen between strangers.

We talked about family. I shared how my parents had escaped China as children, grew up in Taiwan, and eventually came to the United States. He told me his family's story. While I have forgotten many of the details, I do remember its spirit.

His family had been among the millions of ordinary Germans who lived through Hitler's rise. They weren't the fanatical supporters we studied in American history classes. They didn't cheer at rallies or wear swastikas. But they also didn't resist. They went to work, raised their families, and looked away—some from feeling powerless, but much from not wanting to lose jobs, safety, or comfort.

The guilt that followed wasn't just societal. It was deeply personal. He mentioned there was a specific German word for this feeling. Later, I looked it up: "Vergangenheitsbewältigung"—the struggle of overcoming the past. It's the process of resolving the guilt of being on the wrong side of history, and it has its own Wikipedia article.

That conversation planted a question that has only grown more urgent: What will future generations say about how we responded to our moment of testing?

America's Ongoing Reckoning

While my parents came from China and Taiwan, I was born and raised American. I recognize that American history is littered with moral failings we're still working to resolve: the genocide of Native Americans, slavery, Japanese American internment during World War II. (As a side note, Canada also implemented Japanese internment. Marsha's dad experienced this firsthand.)

Despite lessons from this troubled past, we as Americans are facing new assaults on our democratic system. We're witnessing unprecedented authoritarianism, disinformation campaigns, and the systematic erosion of democratic norms. Yet I see many people choosing to look away—not from malice, but from fatigue, fear, or the belief that others will handle these problems for them.

This is how democracies can die. In this case, there’s not a dramatic coup but rather just the accumulated silence from those looking away.

Living History, Not Just Studying It

The past months have reminded me that we're not just studying history. We are living it. I've written about the President targeting public servants like Chris Krebs through executive order and threatening CBS and the free press with a bogus lawsuit (which got settled through a suspected payoff and future airtime). I've documented many instances of corruption.

But the pattern extends far beyond what I've covered: mass deportations despite public opposition, tax cuts for the wealthy at Medicaid recipients' expense, and participation in the Iran/Israel conflict against majority will. These aren't isolated incidents. They are symptoms of a system where power operates without accountability.

That's why I've marched alongside people holding #NoKings signs. We are citizens, not subjects. Power must remain accountable to the people it serves.

In preparing for the #GoodTroubleLivesOn protest, I read John Lewis's words to guide me: "Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble." Every call to a legislator, every town hall appearance, and every protest are my attempts to embody that spirit.

Why Civic Engagement Matters Everywhere

I understand the skepticism about my approach. I live in a blue city, in a blue county, in a blue state. What difference does my voice make here?

But democracy isn't a spectator sport, and it doesn't function only in swing states. When we normalize civic disengagement anywhere, we weaken the entire system. I hope my participation here models democratic behavior for others so we can keep our democratic muscles strong. Citizenship requires more than voting every few years.

Moreover, even in aligned communities, we face local challenges that demand attention, including how to manage the homelessness crisis here in Portland. (And this will likely be a subject of a future Substack post!) Democracy works best when citizens stay engaged at every level.

Finding Your Own Way to Participate

I don't expect everyone to join me in writing, calling legislators, attending town halls, or protesting. Not everyone can. Not everyone should. But I hope people will ask themselves: What do I care about and what am I willing to do?

Civic engagement extends far beyond marches. It includes voting in every election, having difficult conversations with friends and family, showing up at community meetings, and holding power accountable in whatever way you can manage.

Change can be frustratingly slow. At a recent protest, a speaker reminded us that no civil rights legislation was ever perfect or solved problems completely. But civic engagement reminds me I'm not alone—that others care deeply about these same issues. Even if we can't change everything today, we're planting seeds for tomorrow.

Our Moment of Reckoning

I believe we're living through a moment that future generations will study intensely. Our descendants will ask what we did when freedoms were threatened, when truth was under attack, and when the vulnerable were targeted.

The German word "Vergangenheitsbewältigung" — struggling to overcome the past — exists because an entire generation had to reckon with their silence. They had to ask themselves: Why didn't we speak up? Why didn't we act? What might have been different if we had?

I don’t want my descendants to be sitting on an airplane explaining away my failings.

That's why I'm committed to civic engagement. Not because I think it's enough, but because I know silence isn't. I believe at least showing up and getting involved in some way is my responsibility as a citizen.

When questioned about how I responded to this moment of testing, I want my answer to at least be: I showed up. I spoke out. I tried.

What will your answer be?