Democracy in Trifecta, Gerrymandering, and Walkouts

Reflections from Oregon's Political Battles

Apologies for publishing and emailing this post out-of-cycle on a Friday. News changes so fast in the current political environment that I didn’t want to wait until my normal Sunday publish date because experience has shown me that a lot can change between now and then!

— Stephen Pao

It’s always funny to me how politics operates the same way at various scales. For this post, I wanted to reflect on how politics in the state of Oregon work like our national politics, with an interesting role reversal between the Democrat and Republican parties. Here in Oregon, we’ve had the issues of a trifecta (control of the top office and both legislative chambers) by one party. We’ve had gerrymandering. We’ve had legislative walkouts. And I’ve had to make personal decisions as a voter on how to respond.

With Oregon’s own state politics and our corresponding Republican walkouts, I wasn’t surprised by the recent walkout by Democratic lawmakers in Texas. Within Oregon, we had a similar gerrymandering situation but at a different scale with only one new House seat in play in favor of the Democrats. The Texas mid-term gerrymandering proposal, on the other hand, aims to gain another five House seats for Republicans in the 2026 midterm election. Based on a similar (but opposite party) experience by Oregon Republicans, I see this walkout by Texas Democrats as a "necessary evil" despite some misgivings.

Cutting to the chase, I also reluctantly support the potential countermeasures in both California and New York to gerrymander their state districts in response to actions in Texas and other red states.

How Oregon Taught Me About Political Warfare

Earlier in my life while working, I don’t think I really spent much time or attention on state-level politics. However, as part of retiring to Oregon, I had a desire to gain a better understanding of what happens here.

Once moving here in 2018, I found it odd that Republican legislators were staging multiple walkouts. Early on, I was personally against these walkouts, believing that lawmakers should stay, debate, and persuade — not abandon their posts. But context, as I've learned, changes everything.

As a competing principle, I also oppose gerrymandering, whether it benefits Republicans in Texas or Democrats here in Oregon. Manipulating district boundaries to favor one party undermines the democratic process, regardless of who does it. I’ve written before about my own justice sensitivity, and the gerrymandering just activates something inside of me.

Yet sometimes, principles collide with reality in uncomfortable ways.

The Broken Promise That Changed Everything

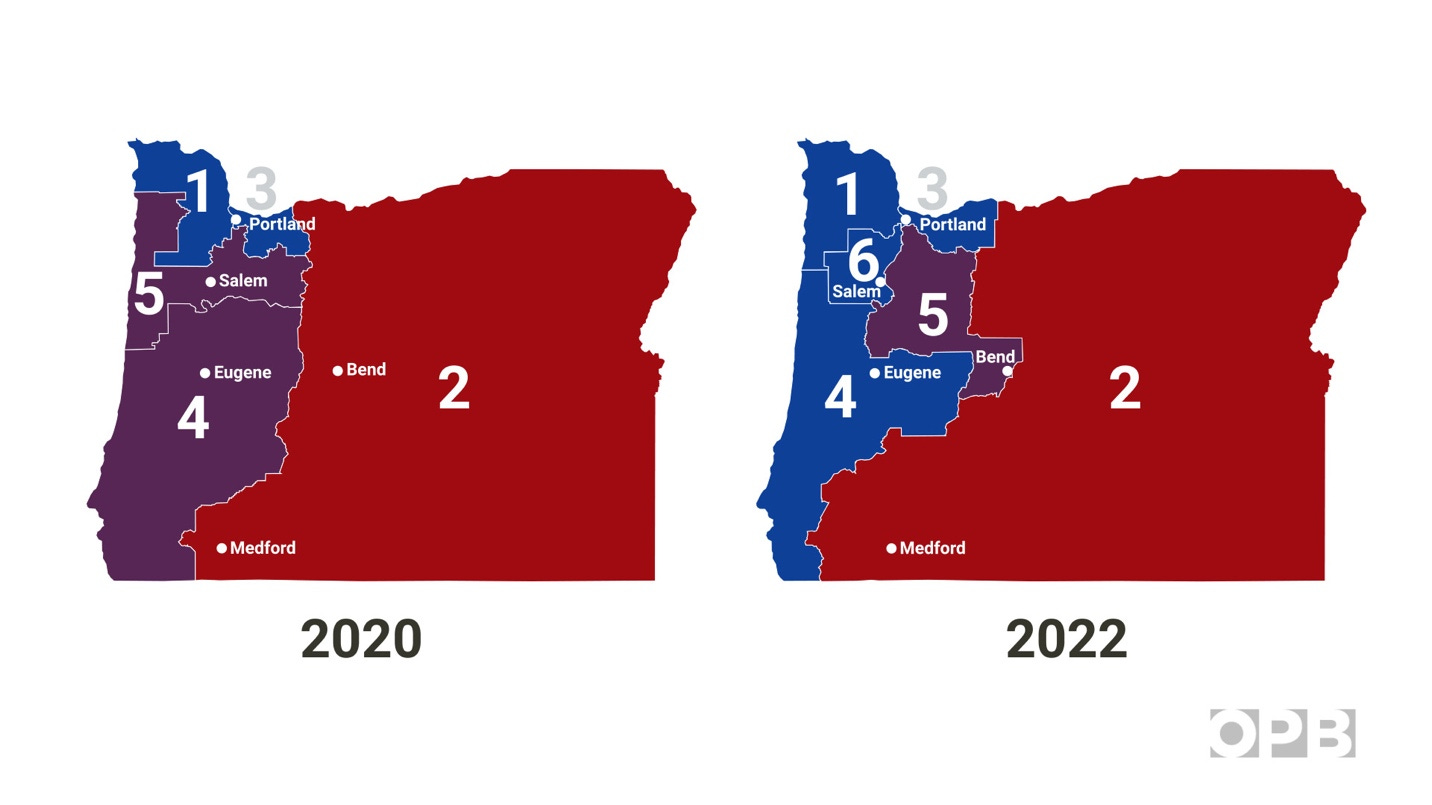

After the 2020 census, Oregon gained a House seat, moving from five to six representatives. Back in 2021, our current governor, Tina Kotek, was House Speaker and broke a promise to give Republicans equal representation in Oregon's redistricting effort. The result was an Oregon congressional map that, while technically legal, is clearly gerrymandered.

The Portland Metropolitan Area is sliced like a pie into multiple districts, diluting community representation. The absurdity hits close to home: even within my tight social circle of people I see regularly, we're spread across four different districts. I'm in District 1 (Suzanne Bonamici), friends 4 miles away in Southeast Portland are in District 3 (Maxine Dexter), friends 9 miles away in Lake Oswego are in District 5 (Janelle Bynum), and friends 11 miles away in Tigard are in District 6 (Andrea Salinas).

Outside Portland, District 4 centers around Eugene (blue), and District 2 consolidates red votes covering a vast region of southeastern Oregon, making District 2 one of the largest geographic districts in the country. Statewide, with this 2022 redistricting, Democrats hold 5 of 6 seats. In contrast, there are 3 Democrats to every 2 Republicans here, so a “fair” map might yield Democrats 4 seats.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project gave Oregon's congressional map an "D" for fairness due to significant partisan bias.

At the time, House Minority Leader Christine Drazen said, "I now realize that all along the plan was to, in fact, get gerrymandered maps through this body no matter what. Oregonians do not deserve this."

When Walkouts Became the Only Voice Left

This betrayal by Democrats on district boundaries cast the Oregon Republican walkouts in a completely different light for me. Since I've lived here, Democrats have maintained a clear “trifecta,” controlling the governorship and both legislative chambers. With such dominance, there's been little incentive for Democrats to engage in bipartisan negotiation, making walkouts one of the few tools Republicans had to be heard.

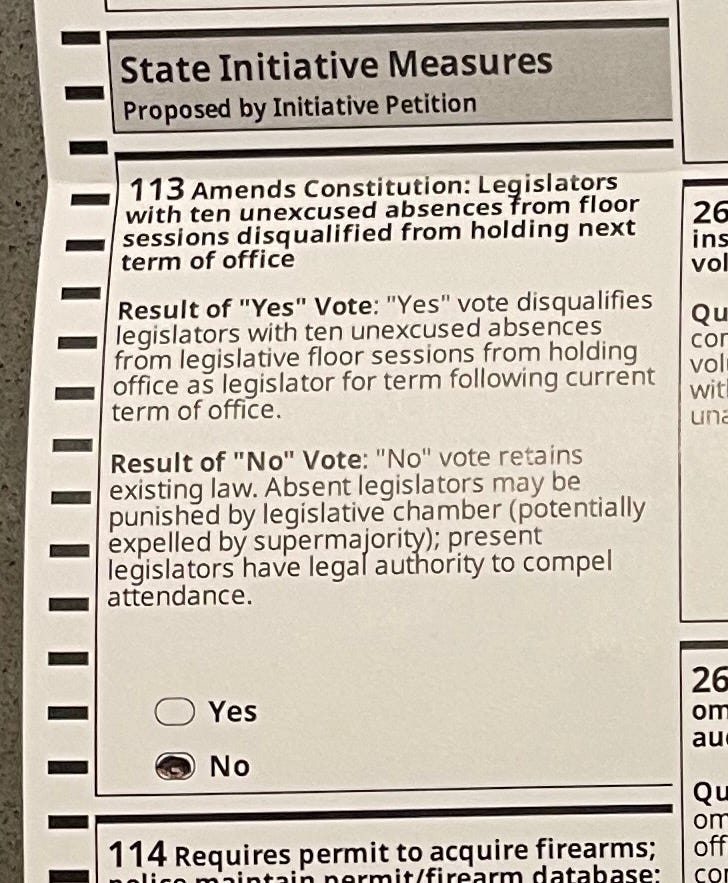

Most Oregonians agreed that walkouts were being overused. However, I believe the solution was misguided. In 2022, Oregon voters overwhelmingly passed Measure 113, which amended the state constitution to disqualify legislators from seeking re-election if they missed ten or more floor sessions. Surprising some of my friends, I voted against it because I was concerned that it would take away walkouts as one of the few tools that could be used by the minority party here in such a partisan environment.

The Oregonian also opposed Measure 113, echoing my concerns about this blunt-force approach.

The measure's first test came quickly. By May 2023, Republican lawmakers felt strongly enough about the lack of bipartisan engagement that they walked out for 40 days blocking eight of them from running for reelection. When they finally returned, bipartisan concessions were made. I appreciated the quote from then Senate Minority Leader, Tim Knopp,

“I think the Democrat majority yielded a lot. That really is what helped make this go ... Essentially what happened is everybody got some of what they wanted, and everybody got some of what they didn’t want.”

— Senate Minority Leader from 2021-2024, Tim Knopp, as quoted in OPB

It's frustrating that it took shutting down the legislature for 40 days to achieve what good-faith negotiation should have accomplished without a shutdown.

The Root Problem: Extremism from Closed Primaries

Oregon's largest voting bloc consists of unaffiliated voters at 38%, compared with 31.7% Democrat and 23.6% Republican.

When I look at the partisanship problem in Oregon, I believe a root cause is more extreme candidates fostered by Oregon's closed primary system, where only registered party members can vote in their party's primary. The primaries exclude the largest bloc of voters in the state.

Why do so many remain unaffiliated? Political affiliation can carry social and economic consequences here. Business owners, for instance, may avoid registering with either party to avoid these consequences, yet this excludes them from publicly funded primary elections.

The impact is profound. Unaffiliated voters have minimal impact on elections, and in two-thirds of Oregon races, the primary winner becomes the general election winner. This system rewards candidates who appeal to their party's base rather than building broader coalitions, and this leads to more division in the legislature. Put another way, you are then left bringing forward candidates that only worry about pleasing their base rather than pleasing the broader base of voters.

There's currently a lawsuit challenging Oregon's closed primaries as unconstitutional, arguing that excluding unaffiliated voters denies them equal voting rights.

Learning from Our Neighbors

The contrast with Washington State is instructive. Washington's legislature functions far more effectively, and I believe their open primary system is a major factor, forcing candidates to appeal beyond their partisan base.

Efforts to reform Oregon's primary system have been repeatedly blocked by legislators seeking easier reelection paths—a clear case of self-interest trumping democratic reform.

On gerrymandering, Washington has implemented an independent commission to assign districts, earning it an A for fairness with the Princeton Gerrymandering Project.

In Oregon, People Not Politicians tried to establish an independent redistricting commission like the one in Washington but failed to gather enough signatures in 2024. They'll try again in 2028, ahead of the 2030 census, and I support them wholeheartedly.

The National Crisis: When Survival Trumps Principle

While Oregon grapples with these structural problems, any reforms are on a longer timeline. However, we face a more immediate crisis nationally because of the current effort to shift Congressional power dramatically in time for the 2026 midterm elections.

Emboldened by Trump's encouragement, Republican legislatures in Texas and other red states are using sophisticated software to redraw district maps aggressively to dilute the impact of Black and Latino voters. In Texas alone, there may be a gain of 5 Republican House seats. Other measures are being considered for other red states, including Ohio, Missouri, Indiana, South Carolina, Nebraska, and Florida. One White House insider described the strategy as “maximum warfare, everywhere, all the time.” There is a scary intent and scale behind these efforts.

Given the urgency of the national situation and the slow pace of structural reform, I find myself reluctantly supporting countermeasures to do temporary, midterm redistricting in blue states like California, Illinois, Maryland, New York, and New Jersey. Fighting fire with fire may be the only way to prevent an unfair power shift that could entrench minority rule for decades.

Where I Stand

My Oregon experience has forced me to evolve on these issues. I still oppose gerrymandering in principle. I understand why lawmakers walk out when the system is rigged against meaningful participation. Long-term, I support open primaries for all federal and state offices. Short term, I reluctantly support the possible countermeasures in California, Illinois, and other blue states triggered by the actions in Texas and other blue states for the midterm elections. I believe these countermeasures should be limited to election cycles before the next scheduled redistricting after the 2030 census. I am reluctant because, In more normal times, I do not believe two wrongs make a right.

However, we're at a critical juncture. The choice isn't between perfect solutions and imperfect ones. It’s between imperfect responses and democratic collapse. The stakes are too high for purity tests. Sometimes defending democracy means making uncomfortable choices. I believe this temporary defense is better than surrendering the field to those who see politics as “maximum warfare, all the time.”

For more context

My view has been shaped by my own experience as a voter in Oregon. There are other views by more prolific political writers on Substack. See Robert Reich’s post today.

Also, Heather Cox Richardson had relevant comments on yesterday’s “Politics Chat.”

If you don’t want to watch the whole thing, skip to timestamp 13:15).

“And I think we have to recognize that we are operating in a in a larger federal system and if that means that the Democrats have to say, ‘OK, if you're going to gerrymander, so are we until we get the system back’, it is worth pointing out that the Democrats have tried desperately to get through laws that stop partisan gerrymandering, and there's a number of ways to do it. And the Democrats all vote for it. And the Republicans all vote against it. So this idea that somehow if the state of California or Illinois or wherever gerrymander is that they're suddenly the bad guys is, you know, that's…that's… right wing propaganda.”

She goes on at timestamp 16:01.

“So should the Democrats do the same thing? I'm on the ‘yes’ side. Even though I am an institutionalist who cares deeply about the institutions, I think one of our jobs going forward is to make sure we lock in a system where people can't do this because it can't gerrymander because it's not good for either party. As I've said before, the people who have control of the gerrymander get more and more extreme because they're not worried about winning their party members. They're only worried about being primary from farther out, and it kills enthusiasm for the system altogether. From those people who are not part of the party that gerrymandered because there's no point in them showing up. And once you lose that system of representation, the only options are apathy or violence. And I I think that's a crappy set of choices. I want stability and the choice in your government.

Washington state has this annoying thing during Presidential primaries where you have to declare (R) or (D). No (I) choice (and it’s on the outside of the envelop where your signature is located). I’ve never voted straight up or down the ticket based on party. And I consider my vote private but as soon as you say that, you get a face full of hateful assumptions, either way. I believe the middle ground voters are a majority in Washington as well. A recent Supreme Court candidate won all counties but King county and lost. Having an inside perspective, it amazes me how many vote uninformed. The social media dominates the narrative and what is deemed truth. How then can we ever hope to reform our system to be a true Republic representing the people?