Dementia is Hard

“To love someone with dementia is to attend a thousand funerals of the person they used to be.”

We have a friend whose dad is suffering from the beginning stages of dementia. I am feeling empathy for her right now.

These feelings motivated me to write about my own experience with my dad through his journey as his brain health failed him. This is an odd post for me to write right now. It is the first post I’ve written about my dad. It happens to be about the end of his life and some of his worst struggles with dementia. (I can attribute this recollection of experiences to the peak-end effect.) In the ideal world, I would have started by writing about the other ways he influenced me during his life while he was cognitively normal. These reflections will come into Substack at some point in the future. Unfortunately, feelings don’t have a storyboard!

Dementia’s beginnings?

In 2006, my dad had a heart attack at the age of 72, after largely ignoring the advice of his cardiologist for years. When the cardiologist showed up at the hospital, he told my dad he was surprised that my dad was still alive after all these years!

While in the hospital after suffering from his heart attack, my dad didn’t want to be treated. His treatment plan involved a quadruple bypass, as well as a procedure on his carotid artery to remove excess plaque. Over several hours-long discussions, my dad shared some pretty interesting insights and feelings about not believing that his whole system could be corrected by simply addressing the blockage in discrete locations. He was also concerned about the systemic effects of the surgery on his lymphatic system. Basically, he was viewing the body holistically, and unfortunately, medical care has become one of specialty. (This will be a subject of a future post!) He wanted simply to leave the hospital and live out the remainder of his life naturally.

There were three reasons he ultimately underwent the treatment. (1) my mom wasn’t ready to let him go, and she begged me to convince him to pursue the treatment. (2) the doctors told me that with dad declining treatment, he would need to sign a release, which could basically disqualify him for further coverage under insurance. (3) my mom was just diagnosed with breast cancer, and it was clear that she would need someone to help her recover from her treatment. Waiting until my dad recovered from his heart attack for him to be that person to support her would be the eventual plan. My dad ultimately decided to go against his own wishes to support my mom and for the good of the family.

One of the (normal) side effects from the surgery was that my dad suffered a minor stroke. A piece of plaque from his carotid artery ultimately broke free and clogged one of his brain capillaries. He had to relearn how to do some basic things.

Of course, we thought at the time that he had recovered just fine. It was only after he passed away that I was able to piece together what was really happening.

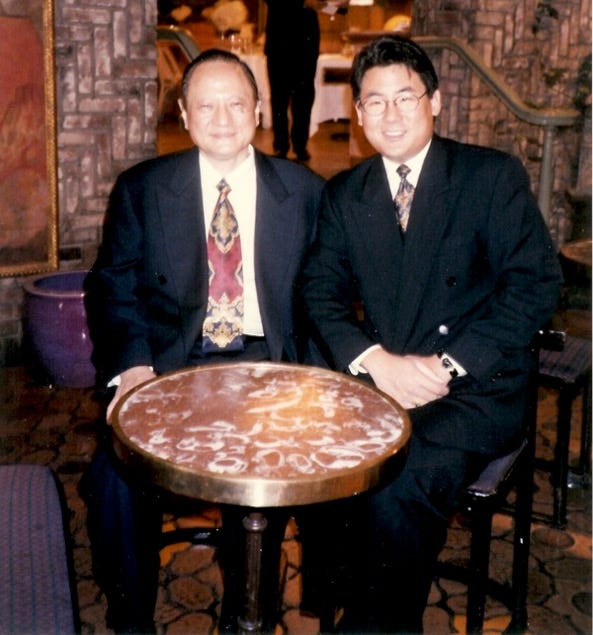

A constant act

After my dad’s dementia had progressed, his neurologist explained to me that it’s very common among high IQ people to do a great job at hiding their condition. This phenomenon likely explained how none of us could see what was going on. Prior to the onset of dementia, my dad was a successful scientist and entrepreneur, having led multiple IPOs and been inducted into the National Academy of Engineering.

After my dad passed, going through his things revealed the effort he took to compensate for the progression of his dementia. From the time he had that heart attack, my dad had every password, PIN code, and security question written down. He had hoarded brochures and receipts from everywhere he went. In the early years, the files were done very neatly. As time went on, paper was just seemingly thrown loosely in desk drawers. It was clear that my dad knew that his brain wasn’t functioning as it used to, and he was working very hard to hide this fact and act normally.

In hindsight, we had some warning signs along the way. My dad mysteriously changed his email address a few times during that period. At the time, I didn’t realize it was because he had forgotten his passwords and the answers to his security questions. It was only after going through notes he left for himself that it became clear to me what had happened.

Once my mom recovered from her breast cancer treatments, he started a business project in China to develop floating wind farms at sea. For most of the time, he was away from Houston and told my mom that the little, remote town where he’d set up shop in China was too backward for her to have a good time. So, he’d return to Houston periodically, but most of his time was spent away from us here in the US. As such, we didn’t really have day-to-day visibility into his deteriorating brain function. In conversation, his logic was always totally sound. What we didn’t realize was that some of the facts informing that logic were incorrect.

Of course, later discussions with the neurologist revealed that dementia hurts the brain’s ability to differentiate dreams from reality. My dad was a dreamer and an optimist. The neurologist theorized that my dad would dream about events and experiences, and his brain was losing the ability to differentiate the dreams from reality.

The net effect was that my dad’s condition caused his own ability to accurately evaluate risks to falter. Towards the end of his life, he had liquidated not only all of his own retirement accounts to support his business ideas but also my mom’s, too. He took out a loan from me as well. I learned later that he took out loans from family members and family friends, too. During this period though, he sounded very rational. I and many others were convinced by the logic, without suspecting that some of the underlying facts were suspect. At the time he died, he left my mom in a very bad situation from a cash-flow perspective.

High function with dementia

What’s interesting is that my dad did understand enough to come home, even with the advanced progression of his dementia. When my mom picked him up from the airport in Houston, she almost cried as airport staff wheeled him out from security in a wheelchair. He had lost a lot of weight and was very weak. With all the weight loss, he didn’t even look like the same person.

The neurologist later explained to us that when dementia progresses, patients lose their sense of taste. The last sense of taste to go is sweet. Nothing tasted good to my dad anymore, and he hadn’t been eating well while living alone in China. We learned later that he had developed a bad habit of snacking on candy.

After getting home, my mom did her best to take care of him. He slowly started regaining weight and doing some light exercises.

I asked my dad how he had even gotten home from China, and he proudly explained to me how he had organized his travel, explaining to the airline that “Dr. Pao is an invalid.” So, he was able to arrange a driver and all the necessary support at the airports, and he did this all by himself!

He also was able to make some really good decisions, even toward the very end of his life. He knew enough to contact the family lawyer and to get both his and my mom’s wills, power-of-attorney, and healthcare directives updated. He signed his updated estate documents on June 24, 2013, less than three months before dying. He re-established contact with a banker they worked with in the past and who still supports my mom to this day, even though her account is well below the level of his normal clients.

Painful Memories

Despite some very high functioning moments from my dad, there were also a set of very painful memories. The intention here is not to dishonor my dad at all but rather to share with others how challenging dementia can be. I am still impressed how much my dad could do even with such advanced disease.

Without a lot of detail, suffice it to say that there were some incidents involving some very understanding public servants. The police had to intervene when my dad had locked himself in a bathroom at Wendy’s and never came out. The fire department had to come to their house after my dad had left the stove on while my mom was out and caused a kitchen fire. Both the police and fire department got involved when my dad needed to be taken to memory care.

The last thing my mom ever wanted to do was to put my dad into memory care. My mom and my dad had known each other since high school. My mom thought she could take care of my dad at home for the rest of his life. A very compassionate family friend helped my mom understand both the safety risk and the toll that was taking on my mom. This friend even vetted the memory care facilities for my mom and found one that was very good and close by. And even after my dad’s death, this friend and her family still look after my mom in Houston. I can honestly say that my dad and mom did something right in their lives to have found and cultivated a friendship like this one.

Memory care

Memory care facilities are depressing. Even the good ones. When we’d go visit my dad, he seemed almost catatonic. I would insist to the staff that they reduce his drug dosages, but the neurologist explained that my dad really wasn’t on high drug dosages at all. The neurologist claimed that once a patient realizes where they are, they tend to “release” all of the tension of having to put on a constant act. He claimed that this causes the patients to just relax and set themselves free. I am still not sure I should buy that explanation because he wouldn’t honor the request to reduce my dad’s drug dosage, likely to make things easier on the staff.

Still, the one thing that helped about my dad being in memory care is that we had good access to a neurologist. I think these consultations helped me support my mom better through this period. Some takeaways.

Don’t take outbursts personally. There were times when my mom would simply want to fluff a pillow or ask how my dad was feeling, and my dad would get angry and want her to leave. The neurologist explained that in this state, my dad would get frustrated and was unable to simply explain that what he really wanted in a given moment was his wife, not another caregiver.

Enjoy simpler moments. We downloaded old Elvis Presley and Nat King Cole songs to my mom’s iPhone, so they could just listen to music together later while in memory care just like they did in the old times.

Remember this is a medical condition. Sometimes, my dad would say nonsensical things that just weren’t true. The neurologist explained that in this state, he could no longer differentiate between what he dreamt about and what was real. As such, he wasn’t pathological in lying but rather just expressing what he experienced in a dream state. There were many examples about his dreamt experiences, including interactions with Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, time he spent in space, and the miracle of how he could be astronomically younger than his kids because of the unique moon cycle he was born in.

Still, I agree with the neurologist that my dad realized where he was, and I think that’s why he ultimately willed himself to die before his second month there. During an exercise session, my dad had a heart attack at the memory care facility and was taken via ambulance to a hospital. Despite DNR orders on his healthcare directive, he was shuttled to the hospital in an ambulance and hooked up to a life-support machine to keep him alive, where we were able to say our good-byes before he finally passed.

When we arrived in the hospital, my dad did awaken a couple of times. During one of these times, my mom asked him if he wanted to disconnect the life-support machine, and my dad nodded his head vigorously. Even on his deathbed, my dad knew what was happening and wanted to go. He passed away on September 11, 2013.

Retrospective

So much of the journey was about reconstructing history, as I didn’t fully understand what was happening in real-time. It’s also important to note that the brunt of this situation was experienced by those who were both geographically closer and provided more emotional support. I remain eternally grateful to everyone in Houston who supported my mom and dad through this really tough time.

Cleaning up after dementia was difficult. There was the financial side. Even with his dementia, my dad could liquidate all the stocks and cash equivalents, and he could borrow money. There was a mess to clean up. We did end up cleaning this up with the support of both the banker and our family friend.

More significant than the financial mess was the emotional mess that got left behind for everyone, including me. For me, one of the biggest challenges was that in this state, my dad was actually no longer the same person that I knew before.My visits were there to see him, support my mom, and to put out fires. The time had passed to hear old stories, resolve past disagreements, or even to gain closure on issues left open.

The “peak-end” effect, mentioned earlier, basically describes how we remember experiences. We remember the worst (and best) parts, and we remember the ending. So, the bummer of dementia is that it can contain both some of the worst memories, and it represents the ending. Remembering my dad properly forces me to remember two, different distinct parts, which were the “peak-end” of his being cognitively normal and the “peak-end” after the progression of dementia. This all circles back to the decision my dad was trying to make for himself after suffering the major heart attack and how he wanted to write his story.

And, as I share genetics with my dad, I know that I, too, am at risk for dementia. One of the reasons I am doing this Substack is to document for my family what I am thinking about to remind them of what I am like now, as I am still cognitively normal! (I have verified this, as I am now a cognitively normal control in a set of observational studies about dementia and early onset Alzheimer’s disease. I will write more about this a future post.))

And, for our friend whose dad is going through this now, my advice is to know that we’re not alone. Try to separate your dad’s memories for yourself into life when he was cognitively normal and life when dementia took over. And remember, the dementia patient is not giving you a hard time. The dementia patient is having a hard time.

Steve - this was really powerful. Thank you so so much for being vulnerable and sharing.

I'm working on a post about dementia so did a search here in Substack and your writing came up. You write beautifully and honor your dad's life and your family's experience. As someone who also had a parent with dementia, I take comfort that we can share our experience here together.